For a person with fishing in their bones, it is exciting to bundle up against the frigid cold, lug heavy gear across a frozen lake in below-freezing, windy weather, to sit on an upturned bucket, focus on a hole in the ice for hours, and find that rewarding, relaxing and exciting. For others, even avid fishermen, ice fishing is a tempting fate. Bob, my son, believes in living each day fully. “You never know what may happen,” he says. One was a scary close call while ice fishing.

For the fun part, when he returned from a frigid day on the lake, a grin from ear to ear replaced the stress lines on his face. His blue eyes sparkled, and his cheeks blushed pink from the cold. “Mom,” he says enthusiastically, “When the water is clear, you can see down to the bottom and watch schools of colorful swim lazily by, sunfish, perch, trout, bullhead, and sometimes a long, thin, northern pike. You can watch the fish swim up and take the bait.” His grin widened to a broad smile when he held out a stringer of fresh-caught perch. He cooked them on a grill.

Here in the Finger Lakes where we live, when Cayuga Lake is frozen, it sometimes looks like the image of ice fishing from the movie Grumpy Old Men, with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau. Or Garrison Keillor’s vivid description of wind-blown wooden fish houses sliding across Lake Woebegone. Some ice fishermen in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York use a blue two-person pop-up, fold-down cloth shanties. They measure about 8′ high and 4’x6′ wide and are made of windproof, tare-proof, waterproof fabric. Spikes hold them from sliding. With a small heater, they are toasty warm. The shanties with rugs beneath and gear on top are dragged across the ice to a favorite spot. Some fishermen choose to walk and tow their gear out on the ice for a mile to reach their favorite fishing spot to avoid risking the additional risk of a vehicle’s weight.

Safety is critical. Danger lurks on spring-fed Finger Lakes waters, which claim the lives of ice fishermen who don’t observe safety guidelines or don’t evacuate if they hear the chill to the bone CRACK as the ice gives way. When fishermen on all-terrain vehicles cross the wind-swept snowy lakes, they often can’t see the soft spots in the ice caused by undergrown springs. Some fishermen who fall through the ice may die because they come to the surface beneath the ice and not at the hole they fell through.

For safety, wear several layers of warm clothing, not Carhart, which absorbs water, a waterproof suit, an inflatable safety vest, and insulated, comfortable boots. Wear ice spikes, a short rope with an ice spike at each end. If you have fallen through the ice, this tool can be lifesaving.

Seasoned fishermen sometimes feel safety equipment is for the inexperienced, that safety lies in checking the depth of the ice to be sure it is at least six inches thick. Many fishermen tell stories of their own close calls, including my son. Storms come up unexpectedly, or the ice gives way. Yes, ice fishing may tempt fate. However, those who have a passion for fishing say the tranquility, the sweet smell of the water and the fish, plus a stringer full of colorful, yellow, and green, perch outweigh the risks. One day, my son’s grim face reflected that a recent ice fishing trip had not been another day of fun in the sun. His speech was more rapid than usual.

“It was bright and early one chilly 22˚ morning when I felt the lure of the lake snag me. Work had been stressful. I needed a day on the lake to chill out. I tried to reach several friends to see if they wanted to go ice fishing, but they worked that day. Since it was such a beautiful day, even though I knew it was unsafe to ice fish alone, I loaded my gear into my truck and was on my way. I checked my list: fish shanty, auger ice chest, ice, rod, bait, bucket, heater, food, and water for hydration. The wind on the lake is often brutal, so I put on several layers of clothes and well-insulated boots.

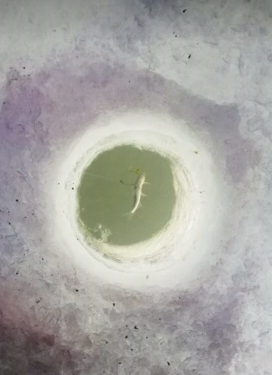

When I arrived at the upper end of Cayuga Lake near Union Springs, I unloaded my gear from my truck, piled it on the fish shanty, and pulled my gear across the ice. There was an island about half a mile offshore. I knew a good spot to fish not too far from a little island. Once there, I used my manual auger and drilled an 8″ wide hole in the ice. I didn’t see any fish, so I drilled another hole reasonably close by. The ice was about six inches thick at the first two holes. I moved to the end of the island and drilled the third hole. After several turns of the auger, the ice was soft, mushy, and only about three inches thick. I heard the dreaded sound as a crack ricocheted across the ice. The sound sent chills up the spine. In an instant, the ice gave way, and I dropped into the frigid water. I knew I had to keep my wits about me to survive. First, I tried to get to the island, but the ice broke away as I attempted to grasp it, so I turned and faced the shore. I was thankful to see a couple fishing at the edge of the lake. I waved and shouted, but they didn’t respond.

I knew to survive, it would take all the stamina I could muster, and in the icy water, I wouldn’t last long. I grasped the ice to pull myself out. I didn’t have ice spikes at the time. My leather gloved hands slipped, my gloves frayed, and my hands bloodied. I repeatedly attempted to grip the ice, but the ice couldn’t support my weight, and it gave way under my hands. My whole body shook. My strength was running out fast. With every ounce of energy I had, I propelled myself up. With one last lunge, I grabbed onto the ice and launched onto the ice.

Once on top of the ice, I was still in imminent danger. With knees shaking, I struggled to stand. I was relieved to be free of the frigid water, but only momentarily. My heart sank when the ice gave way, and I plunged into the water again. The couple onshore was oblivious to my struggles as I fought to survive. My endurance faded fast. I made one last attempt. This time I thrust myself on top of the ice. I crawled on my belly with legs splayed to distribute my weight more evenly. I hoped the ice would hold until I made it to shore.

Once onshore and out of the water, my wet pants froze stiff in an instant. I cut them across the knees with my knife, so I could bend enough to walk. I knew I was in crisis when I started to vomit; hypothermia had set in. My body was shutting down far too fast. I was at risk of painful frostbite or death. Thinking about my wife and daughters kept me moving. Just as I reached the shore, a man and his son arrived. When the man approached, I saw deep concern in his eyes. He wanted to call an ambulance to take me to the hospital. I refused transport, saying I lived just around the corner. Not true. I asked him to help me take off my frozen clothes and start my truck, which he did. With dry clothes on, I shook uncontrollably as I climbed into my vehicle. I called Kim, my wife, and told her I was on my way home. The average 30-minute drive took me 20 that day. I knew I drove too fast, but all I could think about was reaching home. The windows of the crew cab steamed, and I shook all the way home. The drive felt endless.

Once at home, Kim gave me a cup of hot chocolate and helped me into a cool shower, which felt like pins and needles from head to toe. We all huddled together until I warmed up, and the shaking stopped. All I could think about was retrieving my gear. I saw the look in Kim’s eyes when she pleaded with me not to go. She’d asked how much the equipment was worth. I told her only a few hundred dollars. She asked if the risk of retrieving the gear was worth taking. I replied, I could buy more. I’d already called my friend, Jeff, who agreed to help me recover the gear.

When we arrived at the lake, I walked, then crawled on my belly toward the shanty with a braided nylon rope around my waist and a treble hook to snag the gear. Jeff, onshore, held the other end of the line, ready to pull me back. When I got close enough, I threw the treble hook toward the shanty about 75-100 feet away but missed. On the third try, the treble hook stuck in the side of the shanty. I wasn’t worried. A bit of duck-tape would easily fix the hole.” Jeff called “Ready?” I held the rope, and Jeff pulled the shanty, the gear, and me back across the ice to shore.” Fortunately, the ice held.

When we arrived at the lake, I walked, then crawled on my belly toward the shanty with a braided nylon rope around my waist and a treble hook to snag the gear. Jeff, onshore, held the other end of the line, ready to pull me back. When I got close enough, I threw the treble hook toward the shanty about 75-100 feet away but missed. On the third try, the treble hook stuck in the side of the shanty. I wasn’t worried. A bit of duck-tape would easily fix the hole.” Jeff called “Ready?” I held the rope, and Jeff pulled the shanty, the gear, and me back across the ice to shore.” Fortunately, the ice held.

Bob said on a cold night the following winter, “the lure of the frozen lake beckoned. I’d promised Kim I wouldn’t ice fish alone again. I’d wear my inflatable vest, my waterproof suit, a Christmas gift from Kim, and ice spikes.” I could feel his longing to be on the lake in his ice shanty, sitting on his upturned bucket. Yes, I knew he’d keep a sharp lookout for sudden storms and listen for the ominous sounds of the ice cracking. He says, “When the crisp fresh air tickles the nose, ah ice fishing. It is a super de-stressor. No phones ringing, no stress, peacefulness.”

I asked his words of wisdom for fellow ice fishermen. He said he’d learned a lot since the incident 10 years ago, for example, “Take a spud to check the ice.” He explained, “it is a sharp ice pick on the handle. Stab the ice in front of you walk on it. If water starts coming through, turn back. Be safe, and always take someone with you.”

By Barbara Schramm RN CHTP, Mindbdyhealth@yahoo.com – Barbara, a Mind-Body Health Care practitioner for over 35 years, sees the positive impact being in nature has on a person’s health. Stress is a top cause for illness. Being outdoors is a natural, non-toxic, de-stressor. She says of fishing, its more that dipping a line in the water, it teaches you about life.

By Barbara Schramm RN CHTP, Mindbdyhealth@yahoo.com – Barbara, a Mind-Body Health Care practitioner for over 35 years, sees the positive impact being in nature has on a person’s health. Stress is a top cause for illness. Being outdoors is a natural, non-toxic, de-stressor. She says of fishing, its more that dipping a line in the water, it teaches you about life.

Her love of nature came naturally at early age and through her father’s guidance. He taught her how to tie flies which required patience and dexterity. He took her stream, and deep-sea fishing. Barbara has since fished from Nova Scotia to Florida. Her two sons, two grandsons and a granddaughter are avid fishermen. She lives in the Finger lakes region of New York.

All photos are the courtesy of Robert Schramm