Decades ago, as Ed Enamait and other biologists surveyed the Potomac River for walleye, smallmouth bass, muskie and other freshwater game fish, they discovered a disturbing trend. Every year during the 1980s and ’90s, their electroshocking gear brought fewer stunned eels to the surface. “It was troubling,” said Enamait, then a fisheries biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “And it just kept going down.”

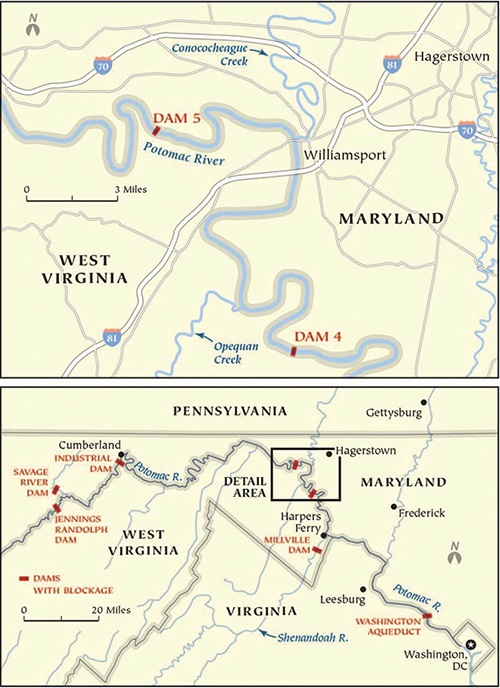

Enamait voiced his concern about the decline within the department, and when two small hydroelectric dams on the Potomac were up for relicensing in 2002, the DNR weighed in to help the eels. They asked that special passages be built for them at Dams No. 4 and No. 5, just 13 miles upstream of the river’s confluence with the Shenandoah River.

Today, Enamait is still worried about eels — and still waiting for them to get passages at the two Potomac dams, a project that’s become mired in federal bureaucracy.

“We carved the presidents’ faces in Mount Rushmore in 14 years,” said Enamait, who retired in 2006. “But we can’t get these eel ladders. It’s kind of frustrating to me.”

There may be a glimmer of hope: Federal officials believe they may have finally cobbled together enough money to build a passage at Dam No. 4, and construction could begin as soon as next summer.

But even if construction goes ahead, the upstream movement of eels will still be hampered by Dam. No. 5, just 13 miles upstream, and recent studies have suggested that eels may face greater challenges downstream than previously thought.

Enamait attributes the slow progress to eel apathy. “It’s not like a bunny rabbit. It’s a slimy critter that probably most people are afraid of.”

But American eels are a species he and other biologists think is important to the river’s water quality. It also has a remarkable and challenging life cycle that is complicated by the presence of dams. “I’m surprised they’re around at all, myself,” Enamait said.

Eels spawn in the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, but their larvae drift on ocean currents and are dispersed along the East Coast, transforming into clear “glass” eels just a few inches long as they approach the continental shelf.

They gain pigmentation as they become larger “elvers” and then adult “yellow” eels which settle into coastal waters or swim up rivers where they spend most of their lives. After a decade or more, egg-laden adult female, “silver” eels, which can reach lengths of 3 feet or more, migrate downstream back to the Sargasso to spawn, and ultimately die.

Eels were once one of the most abundant species in East Coast rivers, accounting for a quarter of the biomass in headwater streams. But their populations have plummeted in recent decades and vanished from some areas altogether. Dams that block or hinder migrations into historic habitats, overfishing, pollution, infestation by exotic parasites and climate change have all been cited as contributing factors in their decline.

They have twice been considered, and rejected, for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature includes the American eel as “endangered” on its Red List.

A stock assessment released in October by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, a panel of state fishery officials that manages migratory species along the coast, classified the coastwide eel population as “depleted.”

Eels are considered a priority species for restoration, especially for fish passage efforts, under the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement.

“No doubt eels definitely are impacted by dams,” said Stuart Welsh, assistant unit leader of the West Virginia Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, a partnership between state and federal agencies and West Virginia University. “They do deter upstream movements, and some dams have larger impacts than others.”

Very large dams, like those on the Susquehanna, are virtually impassable without ladders, but some eels manage to slither up or around smaller unmodified dams like those on the Potomac and Shenandoah. Small dams nevertheless have an impact; surveys by the Maryland Biological Stream Survey show dramatically reduced eel densities in Potomac River tributaries above Dams Nos. 4 and 5.

But lost habitat is only part of the problem caused by structures. The sex of an eel is not determined until later in life, and research suggests that eels in areas with dense populations tend to be males, while those that reach sparsely populated headwaters are almost exclusively females.

By limiting access to those areas, dams may be reducing the number of females available to spawn.

A study on the Hudson River seemed to confirm this, showing that the concentrated populations of eels below dams were predominantly males. In addition, eels trapped below dams are often in poor condition, possibly because of increased competition with other eels for food and habitat.

Welsh, who has monitored eels using passages on the Shenandoah River, said well-designed passages would likely boost the numbers of eels that get above Dams Nos. 4 and 5 on the Potomac. “They do get upstream without those ladders,” Welsh said, “but the passages will enable the eels to get upstream easier.”

When the eelways were first planned for the dams 15 years ago, no one dreamed it would take so long for them to become a reality.

Back then, the first eel passages in the Bay region were becoming a reality in the nearby Shenandoah.

As part of its federal relicensing agreement that same year, Allegheny Energy — which has since merged with First Energy — had committed to building eel passages at its five dams on the Shenandoah River. The first, the Millville Dam on the Shenandoah River, not far from Harpers Ferry, opened in 2003.

It is a simple, covered aluminum trough less than 2 feet wide and about 6 inches high. Inside is a sort of slalom of vertical PVC pipes, which allow the eels to slither up the passage, which rises from a slackwater pool below the dam at a 45 degree angle. It cost $75,000 to build and install.

Since it opened, around 30,000 eels have passed over the dam, according to Welsh. The power company quickly followed with eel passages at its four other Shenandoah dams. It also agreed to stop operating the dams at night during the fall, when mature eels migrate downstream, to reduce the number of them being killed in the power-generating turbines.

At about that time, Allegheny, which also generated power at the two Potomac dams, also agreed to put $150,000 aside to design and construct eel passages there as well. With those, and the Shenandoah passages in place, biologists thought eels were about to regain access to nearly all of the Potomac watershed.

But today, if migrating eels fail to make a left turn into the Shenandoah when migrating up the Potomac, they soon encounter Dam No. 4, an 18-foot-high structure near Williamsport. Built in 1832, it was one of eight dams constructed to divert water into the adjacent Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

While most of the diversion dams were breeched by storms over time, Dams 4 and 5 were converted to small hydroelectric facilities in the early 1900s. The historic structures are owned by the National Park Service, as part of the C&O Canal National Historical Park. Although the utility put aside money to help build eelways, the federal government was actually responsible for constructing the eel passage.

“The industry has really done their part,” said David Sutherland, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Chesapeake Bay Field Office who is overseeing the project.

But back then, building eel passages was still a novel concept, and government biologists initially thought that passages at the two dams would cost the same as the Millville structure. They failed to account for the fact that the eelways on the Potomac dams were impacting historic structures and were in areas with heavy visitor use.

Access to Dam No. 4, for instance, was limited by an old historic bridge that had no electricity and wouldn’t support construction equipment — all factors that caused costs to skyrocket.

By the time the agencies had paid for studies, additional engineering and tackled the more complex design issues, there was no longer enough money to actually build the eel passages. The project languished for years.

“It should have been taken care of in the early 2000s,” Sutherland said. “The early missteps [are what] made it so difficult for us.”

Fed up with waiting, Enamait this spring wrangled a meeting with Department of Interior officials in Washington, DC. State and regional agencies, along with nonprofit groups, also began to press to get the project moving.

In recent months, agencies have cobbled together roughly $150,000 — at least on paper — to pay for an eel passage at Dam No. 4. Sutherland noted that the paperwork is still being processed.

If all goes well, he said, work on the eel passage should begin this summer. But, he added, it’s only part of the project. Getting eels above Dam No. 4 will give eels easier access to some sizable tributaries, including Conococheague Creek, which stretches all the way into Pennsylvania. But Dam No. 5 is only 13 miles upstream on the Potomac and still blocks most of the 17,000 miles of the river’s upstream tributaries. The eel passage needed at Dam No. 5 is also more complex, and is expected to cost more than $350,000.

Sutherland said he is hoping to snare other funding options like mitigation money from a transportation project to help pay for that, but the outlook remains uncertain.

He’s also hopeful that things may improve for eels downstream as well. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service eel survey conducted several years ago suggested that the Washington Aqueduct and dam, operated by the Army Corps of Engineers to supply water to the District of Columbia and surrounding suburbs, may be taking a toll on eels moving both upstream and downstream in the Potomac.

A significant number of eels were caught at the base of the dam near the Maryland and Virginia shores trying to find a way to migrate upstream during spring high water flows.

Sutherland said some eels are using the C&O Canal when trying to get around the aqueduct and dam, where they are easy pickings for predators.

“There are plenty of raccoons, foxes and others that would love to have a nice tasty little eel to take back to the den for dinner,” he said.

Another study also found that some eels migrating down the Potomac are also being sucked into the aqueduct’s intake pipes, which is almost certainly lethal. Corps officials have said further study of the aqueduct’s impact is necessary, and have recently signaled a willingness to address the problem.

“We would be willing to work toward a project, but we would need to ensure it does not affect our operations or negatively impact our ability to meet our [water] customers’ needs,” said Sarah Gross, a spokeswoman for the Corps’ Baltimore District, in an email.

Sutherland credits the persistence of Enamait, along with others he has helped coalesce around the issue, for the recent movement.

After years of disappointment, Enamait is guarded about the projects. He said he gives funding for Dam No. 4 only a “50-50” chance of materializing, and is less optimistic about the upstream dam.

But he hopes they become reality. It’s tough to get attention for a fish that looks like a snake, he’s learned: “Most of the people who catch one would probably cut its head off.” Eels, he stated, need all the help they can get.

Eels & Mussels

One of the reasons biologists are interested in rebuilding eel populations in the Bay watershed is research that shows they, indirectly, help benefit water quality.

Studies have found that eels are critical for the reproduction of the Eastern elliptio, the most abundant freshwater mussel in many Northeastern rivers.

Mussels release their larvae, or glochidia, into the water where they attach to fish “hosts.” The larvae attach on the hosts as parasites until they transform into tiny mussels and fall to their home in the stream bottom upstream, where they can live up to 100 years.

While many mussels use a variety of hosts, lab work indicates that the eastern elliptio relies primarily on eels. For millions of years, that was a safe relationship as eels were one of the most common freshwater species, but the building of dams has changed the equation.

In the Susquehanna River watershed, where eels have been totally blocked by large hydroelectric dams until recent reintroduction efforts, Eastern elliptios are considerably less abundant in nearby rivers, and remaining populations are dominated by large, old mussels, with little sign of reproduction.

Gone with them is a huge potential water-cleansing capability. Each adult mussel can filter about 18 gallons of water a day as it feeds, removing pollutants in the process.

Surveys on the Potomac River upstream of Dams No. 4 and 5, where eel numbers are greatly reduced, have also shown a reduced number of Eastern elliptio mussels, according to USF&WS biologists.

By Karl Blankenship is editor of the Bay Journal and executive director of Chesapeake Media Service. He has served as editor of the Bay Journal since its inception in 1991.