It’s been a tough season for waterfowl hunters around the Chesapeake Bay, and it’s going to get even tougher next season. Concerned by a sharp drop seen last year in the Atlantic population of Canada geese, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has ordered a shortening of the 2019–2020 hunting season for the migratory birds and a cutback in the number that hunters may take daily.

It’s been a tough season for waterfowl hunters around the Chesapeake Bay, and it’s going to get even tougher next season. Concerned by a sharp drop seen last year in the Atlantic population of Canada geese, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has ordered a shortening of the 2019–2020 hunting season for the migratory birds and a cutback in the number that hunters may take daily.

Federal wildlife regulators also have tightened next season’s limits on hunting for mallards, one of the most abundant ducks in the world, as they seek the cause of a long-term decline in their numbers across eastern North America.

That’s unhappy news for waterfowl hunters in the Bay watershed, who have already seen a falloff in this migratory goose season, which ends Saturday in Maryland and ended Jan. 27 in Virginia. Mild weather through the fall and most of this winter brought fewer Canadas to the region from north of the U.S. border. There have also been few if any juvenile birds— which are less wary of hunters’ decoys than their elders — in the visiting gaggles.

The hunting season for migratory Canada geese, which for several years has run 50 days in two stretches from November through January, is slated to be reduced next season to 30 days. For hunters in Pennsylvania and New York, the daily “bag limit” will drop from three to two. But around the Chesapeake Bay — in Maryland, Delaware and Virginia — the limit will go from two to just one a day.

Duck hunters will see their daily quota of mallards reduced from four to two all along the Atlantic Flyway, which stretches from Canada to Florida.

Some have questioned the regional variations in cutbacks ordered on geese, but most hunters — at least those attuned to the explanations from wildlife agencies and conservation groups — seem resigned.

“The numbers are down … so we have to bring those up,” said Steve Myers, executive director of the Maryland Waterfowlers Association. “In order to bring those up, we have to reduce the harvest.”

“The numbers are down … so we have to bring those up,” said Steve Myers, executive director of the Maryland Waterfowlers Association. “In order to bring those up, we have to reduce the harvest.”

There are more than a dozen distinct populations of Canada geese across North America, and most are holding their own. The Atlantic population nests throughout much of Quebec. In fall, those birds fly south, spending the winter at sites from New England to South Carolina. But the biggest congregation is near the Chesapeake Bay, on the Delmarva Peninsula.

Wildlife biologists say the Atlantic population is down primarily because of unfavorable weather conditions on their Canada nesting grounds. Seven of the last 10 years have seen below-normal reproduction, but a particularly late thaw last spring prevented many birds from nesting and resulted in very few goslings hatched.

Biologists who canvassed the primary breeding area managed to find only 30 newly hatched birds among the 3,000 geese they captured and banded —the lowest percentage recorded in two decades of such fieldwork, according to information supplied by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

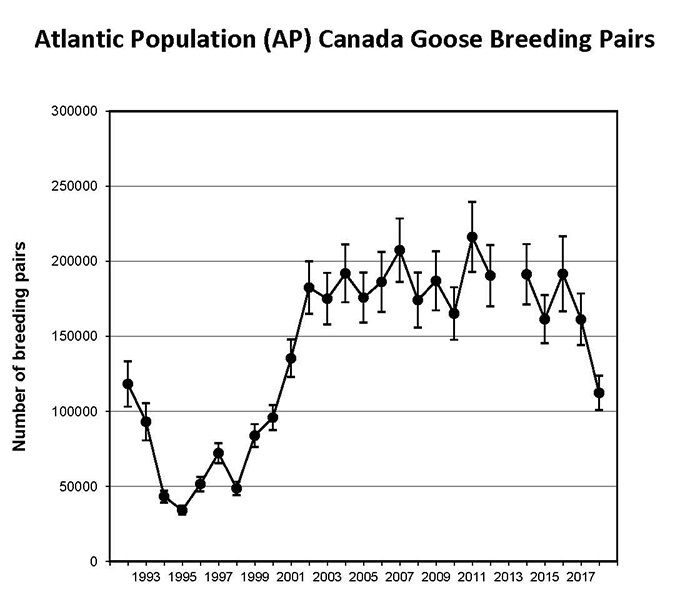

Adding to scientists’ concern, their annual aerial survey of the nesting grounds tallied 112,000 breeding pairs of geese last spring, the lowest since 2000, according to the DNR. The 2018 breeding pair population was sharply lower than the 161,000 counted in 2017 — and far below the nearly 200,000 seen in 2016.

The federal management plan for the Atlantic population of Canada geese requires tighter hunting restrictions when the breeding population falls below a three-year running average of 150,000 pairs. With last year’s plunge, that average fell to 155,000. Although not low enough to trigger a mandatory cutback, authorities decided to act, with the hope of stemming the decline. The Fish & Wildlife Service acted on the recommendation of the Atlantic Flyway Council, made up of wildlife regulators from Eastern states as well as their counterparts in Canada’s provinces.

The 2018–2019 Canada goose season dates and bag limits were already set before the data from last spring’s surveys showed the big drop in breeding pairs. So, while next season is the earliest the rules could be changed to address the decline, the DNR launched a social media campaign —“one and done” — this season urging hunters to voluntarily refrain from taking more than one migratory goose a day.

Hunting only takes out about 10 percent of the breeding population in an average year, according to Josh Homyack, waterfowl project manager for the DNR. But by shortening the season and reducing the bag limit next season, authorities hope to reduce the loss by half.

“Hunting is not the culprit for why the population is down,” Myers said, but hunters have a big stake in being part of the remedy. The last thing they want to see, he added, is to have Canada goose hunting shut down altogether, as it was in 1995, after U.S. and Canadian biologists saw a 75 percent decline in nesting geese over the previous seven years. That hunting ban lasted six years before the population had recovered enough to lift it.

Waterfowl hunters do have the option to hunt longer if they target “resident” Canada geese. Those birds, which do not migrate to and from Canada, can be hunted in September, before the migratory birds arrive, and also in late November and again from late December until March 9 — though only in counties inland from the Bay, away from where the migratory birds congregate.

Myers said he recognized that those on the Delmarva Peninsula who depend on the migratory goose hunt for income during the winter months will be hurt by the restricted season. And since it takes newly hatched Canada geese three to four years before they’re mature enough to breed, restrictions are likely to remain in place for more than just one season.

“It’s going to be a hardship for them,” he said, “but we’ve been here before. We never thought we’d be back here again, but Mother Nature has not been as cooperative as it can be.”

Still, DNR’s Homyack said, “you have to have a robust goose population if you want to have a robust goose hunting industry.”

While federal officials have decreed a cutback in the migratory Canada goose season, they’ve left it up to individual states to determine how to apportion those 30 days between Nov. 15 and Feb. 5. Typically, goose hunting has been allowed for a few days around Thanksgiving, then reopened in late December to run through January. The DNR expects to propose its split schedule of reduced waterfowl hunting dates in mid-February, Homyack said, and to give the public 30 days to comment before finalizing them. A public hearing is scheduled March 6 at Chesapeake College.

“If we have some good nesting years and get a bunch [of young geese] in the pipeline,” Homyack said, “then sometime down the road they’ll show up as breeding pairs and the season will be liberalized.”

It’s not clear, though, why mallards are down, so there’s less hope for a quick lifting of hunting restrictions on them. Aerial surveys have found the population that nests in Canada has been stable, but the breeding population in the northeastern United States has been declining over the last decade, said Jake McPherson, regional biologist for Ducks Unlimited. But surveys don’t indicate that there’s been a drop-off either in reproduction or in survival of mallards, he said, leading to suspicion that the data are somehow flawed.

Some have suggested changes in habitat, cross-breeding with captive-reared mallards or even hunting pressure could be factors. As experts try to identify the cause, again at the recommendation of the Atlantic Flyway Council, the daily bag limit of mallards has been cut in half.

“We know the population itself is declining,” McPherson said. “The question is, what is causing this?”

Wildlife regulators have in the past set season and bag limits for other duck species based on the results of mallard surveys, McPherson said. But with the decline seemingly limited to mallards, regulators have decided to manage them independently, thereby avoiding restrictions on hunting other ducks.

“The whole thing is a practice in adaptive management,” McPherson said. Wildlife agencies are “using the best available science to make these decisions, but sometimes that science is complicated.”

McPherson said he’s an avid waterfowl hunter himself, so the looming cutbacks are “a bit disappointing.” But he said he’s okay with it, because to him hunting is about more “than the number of birds you kill.”

By Timothy B. Wheeler an associate editor and senior writer for the Bay Journal. He has more than two decades of experience covering the environment for The Baltimore Sun and other media outlets. Send Tim an e-mail.

Related:

Restored Oyster Reefs Provide Setting for Chesapeake Bay Fishing Tournament