I’ve seen my share of dead animals.

I understand that death is part of the whole cycle of life; predator and prey relationship. Lion King, Hakuna Matata and all that.

As a hunter and fisherman, I’ve seen death first hand. However, I also pay respect to my harvests that provide healthy food for the family. Nothing goes to waste. I also embrace the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, which focuses on long-term wildlife management.

Recently, I saw the unsavory side of human and animal interactions: illegal wildlife trafficking. It isn’t pretty or respectful.

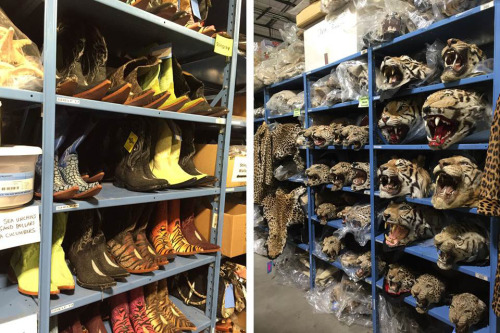

The National Eagle and Wildlife Repository near Denver, Colorado, is what you’d expect from a warehouse – a big building with minimal lighting and endless rows of shelves.

Those shelves hold 1.3 million parts and pieces of wildlife that were illegally trafficked and confiscated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Office of Law Enforcement agents. There are tiger and leopard heads stacked five high; enough stingray boots to fill the wall of a shoe store; and piles of ivory and elephant parts.

The shocking part is that it only represents a thimble full of the animals killed in the sea of wildlife trafficking, which totals $20 billion annually. The heads and hides, bones and horns at the Repository are just a small percentage of items confiscated by the Service’s Office of Law Enforcement agents in their efforts to fight illegal wildlife trafficking into and out of the United States, including the Pacific Northwest and Hawaii.

It’s a fight to save wildlife from extinction. It’s a fight against greed.

At the top of the list are rhino horns, which can sell for $60,000 per pound. That means a single horn can bring more than $300,000. It’s more valuable per ounce than gold, diamonds or cocaine. For what? The horns are mostly made of keratin, the same type of protein that makes up hair and fingernails.

That’s a lot of money – not to mention the devastation of a species – for a status symbol or a faux cure for hangovers.

One positive found in the mounds of greed at the repository is the potential for education.

Items are available for loan to educational facilities, nonprofit organizations, and conservation agencies across the United States. Our Office of Law Enforcement staff use the ill-gotten goods to create educational displays in prominent places or as a part of programs at events and schools.

Education is the key to getting ahead of the wildlife trafficking crisis. Hopefully we all can learn more about conservation and embrace the need to save our wildlife. If we don’t, the future is bleak for many species.

“Every 15 minutes an elephant is illegally killed for its ivory,” Sheila O’Connor recently told me. Sheila is the Resident Agent in Charge for Oregon for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Office of Law Enforcement. “Elephants are killed at a rate faster than they can reproduce. And the same with rhinos. Rhinos are also being killed at a rate faster than they can reproduce. You can do the math!”

We’re all too familiar with the equation: Poaching + Illegal trafficking = extinction.

If we don’t stop illegally exploiting elephants and rhinos for their ivory and horns, they will go extinct. The same goes for tigers and leopards, pangolins and primates, and many other endangered species.

Greed or conservation: It’s an obvious choice for me. What about you?

Watch an interview with Agent Sheila O’Connor: http://bit.ly/294M2XX

Find more travel tips and facts: https://www.fws.gov/le/tips-for-travelers.html

General information for travelers: https://www.fws.gov/le/travelers.html

By Brent Lawrence. Brent Lawrence is a Public Affairs Officer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Pacific Regional Office in Portland, Oregon.