As the Earth’s atmosphere and ocean continue to warm under the global threat of climate change, the future of coral reefs looks bleaker than ever before. With rising temperatures comes an increase in mass coral bleaching events, infectious disease outbreaks, and the process known as ocean acidification. Climate change not only affects the overall health of corals, it also impacts their resiliency. Changes to the frequency and intensity of tropical storms — another side effect of climate change — lead to storm seasons that do a massive amount of damage to coral reefs.

“Storms bring a lot of physical destruction,” said Sean Griffin, a marine habitat resource specialist and corals expert. “The waves, the debris, everything, it all brings a lot of destruction to the reefs, pulverizing the coral, tipping them over … While these are natural occurrences, they’re increasing with climate change. A hundred years ago, these same corals could bounce back. Now, there aren’t as many reproductive corals and many reefs are blanketed with algae that prevent their recruits from settling on the reef.”

Sean works for NOAA’s Restoration Center — a division of NOAA Fisheries’ Office of Habitat Conservation and a close partner to NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration. Together with the NOAA Office of General Council, OR&R and the Restoration Center collaborate through the Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program. Through this program, OR&R handles scientific assessments, known as natural resource damage assessments, to examine the injuries from oil and chemical spills, ship groundings, marine debris, and other marine pollution events. After the Office of General Council negotiates the legal side of things, the Restoration Center takes over and implements restoration projects using the information and recommendations of OR&R’s Assessment and Restoration Division.

During natural disasters, such as hurricanes, the two offices collaborate on response, assessment, and restoration efforts. Over the past few years, with increasing frequency, these efforts have included a number of coral restoration projects. As demonstrated in the 2017 hurricanes that impacted Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Island, the intensity of these hurricanes continues to grow — as does the damage to corals.

Because of the many growing threats to coral reefs, the Restoration Center has been scaling up all aspects of coral restoration in recent years. What does that look like? According to Sean, increasing partnerships with organizations around the world and getting more people involved is the most effective way to vamp up restoration efforts.

“There’s been a lot of restoration work over the last few decades and we’ve gotten pretty good at doing things on a small scale, on a local level. But more work is needed, and on a much larger scale,” Sean said. “Coral reefs are declining around the world. We need to scale things up to deal with these situations, and it’s not just one or two groups that are going to do this. It’s going to have to be a massive ramping up of NGOs [nongovernmental organizations], volunteers, government agencies because at this point it’s basically an all-hands-on-deck situation.”

Coral restoration is just one small part of the overall work that Sean and the Restoration Center team do, but in recent years it has occupied more and more of their time. This is in large part due to above-average hurricane seasons like 2017.

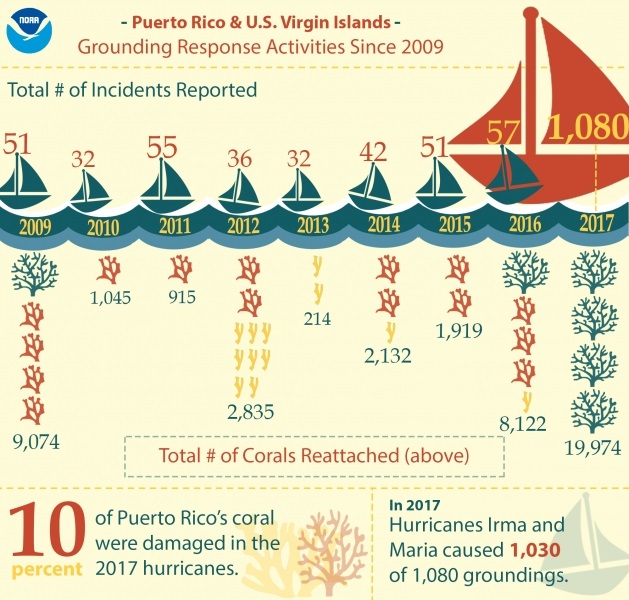

In 2017, the Restoration Center was notified of approximately 1,080 ship groundings in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands — 1,030 of which resulted from hurricanes Irma and Maria. To put that into context, in the eight years prior to 2017 the center never received more than 60 incident reports in any given year.

In the 2017 hurricanes, about 10 percent of Puerto Rico’s corals were damaged. The center focused their initial work on the areas with really heavy damage, assisting FEMA with its mission for coral triage work. During a typical year, the center would do anywhere from 214 coral reattachments to over 9,000. Last year, the Restoration Center reattached a total of 19,974 corals, though their work is still not over.

Initial funding for the post-hurricane assessment and triage work was provided by NOAA and NWFS. The Restoration Center then received funds for a FEMA approved mission assignment that went through July. While damage from the 2017 hurricane season was still left unremediated, the team had to repair and prep the coral nurseries for the 2018 hurricane season.

“More work could be done with more resources,” Sean said, adding that the center will be using funds available from within NOAA and from settlements for two tanker groundings in Puerto Rico in 2009 to continue their work in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands during the coming years.

So what does coral restoration look like?

During a storm, various parts of coral might break off and land on the ocean floor near by. If that coral lands in a clear stable area where it’s able to fuse back onto the reef, it can start a new coral. But if that coral lands in an area that isn’t appropriate for reattachment, such as sand or sea grass, the chances of that coral surviving are very low.

“We’re taking these corals and making sure they have a better opportunity for survival,” Sean said. “If we come get that coral and put it in a better spot, it will have a 90 percent chance of survival as opposed to the 10 percent it had before.”

During hurricanes and ship groundings, Sean and his team can also collect storm fragments for nursery propagation. By bringing coral fragments into nurseries, these corals can be used to grow additional corals that can eventually be transplanted elsewhere to help restore reefs.

While restoration is an important part in countering the effects of climate change on corals, Sean warns that it’s not the “silver bullet” solution.

“It also has to do with reducing CO2 emissions and pollution, and coming at this in a much larger, global scale,” Sean said.

The work conducted by NOAA in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands would not be possible without support from many groups including Sea Ventures, HJR Reefscaping, Sociedad Ambiente Marino (SAM), Vegabajeños Impulsando Desarrollo Ambiental Sustentable (VIDAS), University of Puerto Rico, University of the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resource, and the Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources.

Find out more about corals here:

- Why Are Some Coral Reefs Dying? NOAA Satellites & NOAA’s Coral Program Help Conserve These Vulnerable Habitats

- What is coral bleaching?

- NOAA awards over $8.3 million to advance coral reef conservation science and management

- No safe haven for coral from the combined impacts of warming and ocean acidification