Source mpbn.net: This month we’re launching a new series titled “Beyond 350: Confronting Climate Change.” Over the next year, we’ll be looking at what individuals, businesses, communities and political leaders are doing to plan for its effects in Maine.

Source mpbn.net: This month we’re launching a new series titled “Beyond 350: Confronting Climate Change.” Over the next year, we’ll be looking at what individuals, businesses, communities and political leaders are doing to plan for its effects in Maine.

Spring officially arrived more than two weeks ago, but, as we all know, winter has been slow to release its icy grip. Many lakes and ponds are still frozen. And, in traditional Maine fashion, there are local contests to guess the day it all disappears.

Known as “ice out,” these dates are considered a key indicator of climate change. On many lakes, they’re two weeks earlier then they were 50 years ago, typically in late April or May.

About five years ago, before he was elected to the U.S. Senate, independent Angus King spied a small graph in a newspaper that got his attention. He made copies of it and still uses it as a talking point when he speaks to groups, like this one at the Naples Town Hall.

“The graph, to me, told me everything I needed to know about climate change,” King told the group. “So, I had it put on a little card which I hand to my friends in Washington from time to time, the ones who say nothing is happening.”

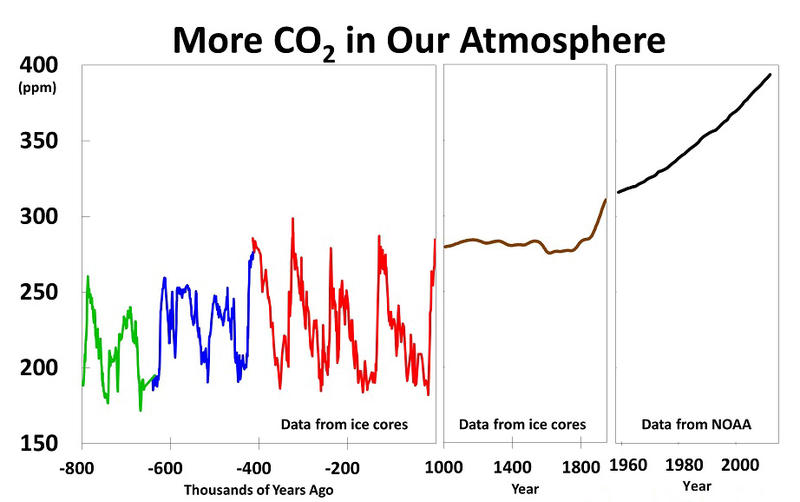

One side of the graph shows carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere over the last million years. The data are based on ice core samples provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. During the same time frame, they show natural variations in CO2 of between 180 and 300 parts per million. But then, in 1860, around the time of the industrial revolution, the line on the graph zooms upward. It’s now just above the 400 mark.

“To me, it’s too much of a coincidence that this starts upward on that sharp incline when we started burning coal, and then later oil, in large quantities all over the world,” he says. “I don’t know about you but I haven’t noticed a big outbreak of volcanoes in the last hundred years.”

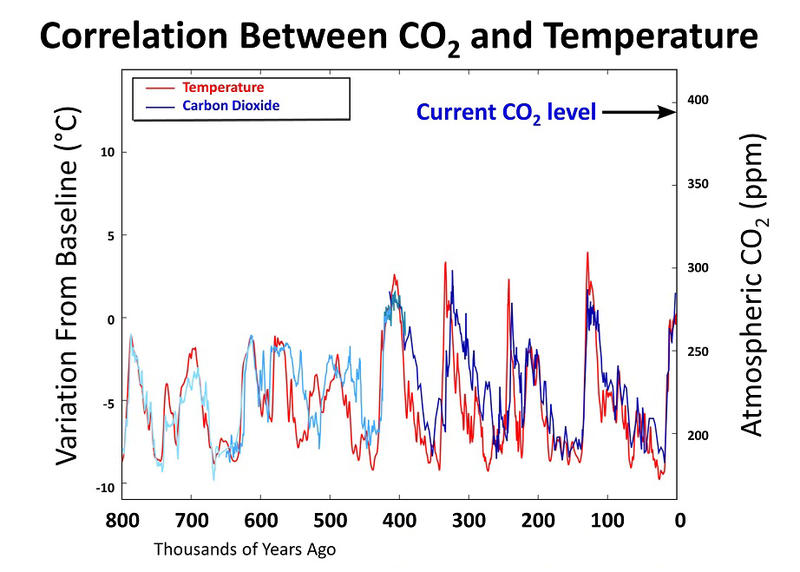

On the other side of the card is a graph that shows the relationship between CO2 and temperature over the last million years. CO2 goes up, temperature goes up. CO2 goes down, temperature goes down. “So this to me says, a) something’s happening, b) people have something to do with it,” King says.

King, who now serves on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee and the Senate Climate Action Task Force, calls reducing the carbon footprint an “urgent priority.”

It’s urgent because climate experts say 350 parts per million is the level needed to sustain the planet. And getting to that number, essentially reversing the line on King’s graph, is akin to putting the genie back in the bottle before irreversible tipping points are reached.

“It’s a challenge that requires international cooperation, including from China and India,” says Sen. Susan Collins.

Like King, Collins has also been speaking out about climate change. Though many of her fellow Republicans in Congress are more than a little skeptical about it, Collins has defended the Clean Air Act and blocked efforts to prevent the Environmental Protection Agency from regulating greenhouse gas emissions.

She has three pieces of advice for making progress on the issue. “The first is to be practical. The second is to enlist more Republicans in the crusade, if you will, and the third is to secure some small victories.”

Speaking at a roundtable discussion in Portland last month, Collins said environmental groups and the business community will have to find common ground on energy efficiency, for example, before tackling the larger more complex policies to address climate change. Above all, she says, it’s essential that the real effects of climate change be connected to what’s going on to people’s daily lives.

And that’s where ice fishermen like Zach Wozich come in. Just three days before Easter, Wozich is ice fishing on Thompson Lake near his home in Casco.

“I wasn’t sure what to expect about the ice, but it’s pretty thick,” I tell Wozich.

“There’s, like, two feet of ice, still,” he says. “The ice will still be out, probably, by the 20th.”

“Of April?”

“Yeah.”

Wozich is happy for a few more weeks to fish for lake trout. But he says he’s noticed something troubling about Maine’s winters in general: big variations in temperatures and snowfall.

“That’s the thing that gets me – whether the winters are really warm or they’re really cold, where you have extreme snow or no snow at all. I’ve been seeing this for the last 10 years at least. There’s got to be a reason.”