Ocean conditions for salmon headed to sea this year are very poor, according to recent NOAA Fisheries research surveys, and have a high likelihood of depressing salmon returns to the Columbia River in the next few years.

The outlook is described in a recent research memorandum from NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center (NWFSC), which has been studying the ecology of young salmon entering the ocean for more than 20 years. The research has helped reveal how conditions in the ocean affect salmon survival and, ultimately, how many salmon complete their life cycle to return to their home streams and spawn a new generation of fish.

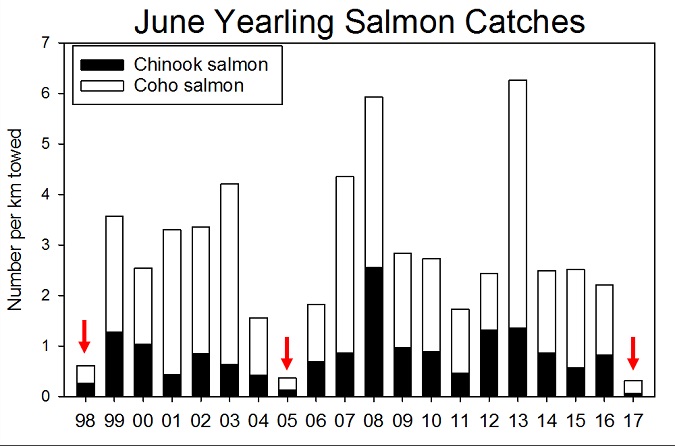

NOAA Fisheries research surveys off the Pacific Northwest this year turned up among the fewest juvenile salmon of any of the last 20 years, an indication that many of the young fish that migrated to the ocean did not survive.

Graphic: Northwest Fisheries Science Center

NOAA Fisheries researchers regularly survey ocean conditions off the Pacific Northwest Coast, focusing especially on factors known as “ocean indicators” that can serve as barometers of salmon survival. They also assess the number and condition of juvenile salmon along the Oregon and Washington coastlines, since the survival of the fish during their first months at sea helps predict how many are likely to survive over the longer term.

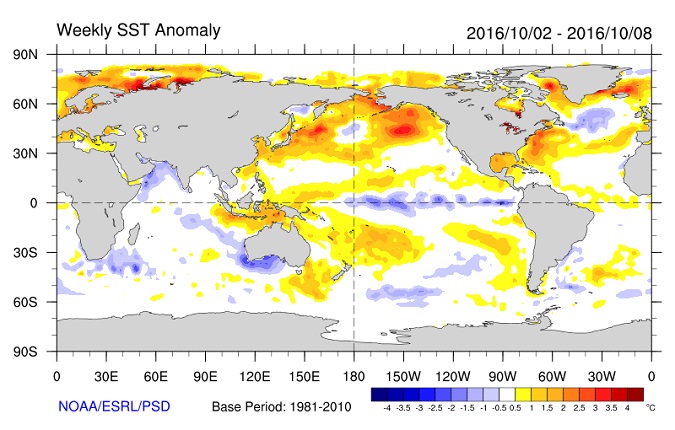

NOAA Fisheries’ many years of ocean research have helped scientists develop online charts of ocean indicators that display the forecast for salmon returns in coming years. In the last few years the indicators have turned largely negative for Columbia River salmon, in large part because of unusually warm ocean temperatures, including the “warm blob,” a large swath of warm water that encompassed much of the West Coast beginning in 2013.

A 2016 map illustrates sea surface temperatures, with darker red representing temperatures farther above average. Unusually warm waters have encompassed much of the West Coast in recent years, affecting the marine ecosystem.

Graphic: NOAA/ESRL/PSD

“This is not just about salmon, however, it’s about an ocean ecosystem that is changing in ways that affect salmon and everything else out there,” said David Huff, manager of the NWFSC’s Estuarine and Ocean Ecology Program. “Remote methods of detecting changes to the ecosystem did not highlight the poor ocean conditions this year. For example, the warm blob has dissipated, so satellite imagery shows near-normal sea surface temperatures. It was only by getting out on the water and sampling directly that we were able to identify and describe local biological indicators.”

Researchers’ catch of juvenile salmon this year was among the lowest in the last 20 years, suggesting that the early survival of young fish was unusually low. Catches of other species such as smelt, herring, and anchovy were also low, a sign that predators such as seabirds near the mouth of the Columbia may have had to rely more heavily on young salmon just entering the ocean.

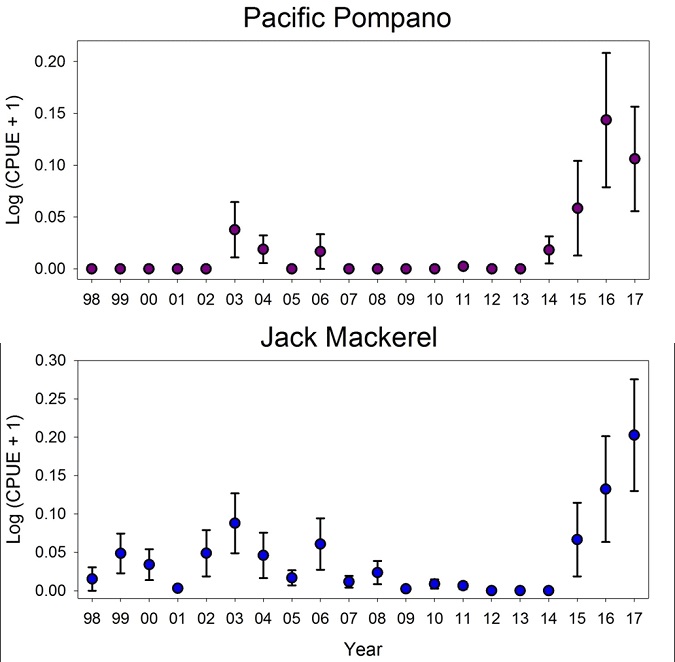

Surveys in recent years have also turned up record numbers of warmer-water species such as Pacific pompano and jack mackerel that previously had been scarce off the Pacific Northwest coast. Increased abundance of these warm-water species can have direct and indirect ecological impacts on salmon.

In contrast to salmon, the warm-water species Pacific pompano and jack mackerel have appeared in research nets in record numbers in the past few years. Jack mackerel often prey on juvenile salmon. Graphic: Northwest Fisheries Science Center

Moreover, warm ocean waters typically carry plankton with less of the fatty nutrients that young salmon need to thrive when they first go to sea, starving the food web from the bottom up. This year researchers noted that chlorophyll, which is a barometer of the plankton that helps sustain higher trophic levels, was at its lowest levels in 20 years.

At the same time, tiny marine crustaceans called copepods that signal favorable conditions for salmon have remained at low levels since 2014, researchers said.

The results indicate that salmon fisheries may face some lean times in the next few years. Biologists will report on 2017 salmon returns later this year, and will issue forecasts for 2018 in early March. Those forecasts will help shape expectations for 2018 fishing seasons.

“While the news is not good, this new information helps us anticipate what’s coming,” said NWFSC Director Kevin Werner. “We cannot change what the ocean is doing in the short term but this scientific information can help us make good decisions about how best to manage and protect salmon in light of these adverse conditions.”

The findings underscore the vast influence the ocean exerts over salmon survival and the importance of providing salmon with healthy freshwater habitat so they can weather poor ocean conditions and take advantage of favorable conditions when they return. That is a central focus of NOAA Fisheries’ recovery plans for threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead.

“As difficult as it is for salmon right now, tribes, watershed groups, and others across the region have worked hard to improve freshwater salmon habitat,” said Michael Tehan, Assistant Regional Administrator for the Interior Columbia Basin Office of NOAA Fisheries’ West Coast Region. “That’s essential for sustaining salmon through these tough times so they can rebound when ocean conditions support it.”

For more information:

Salmon Returns and Ocean Conditions (NWFSC fact sheet)