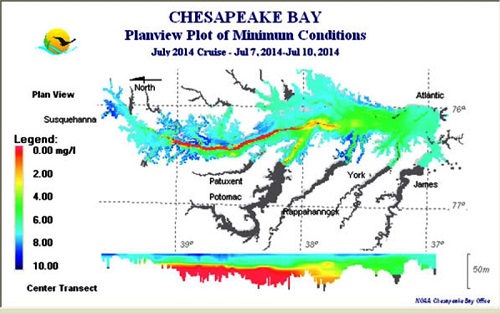

Attention swimmers, especially the beautiful little ones: scientists anticipate a slightly smaller, though still large, dead zone to form in the Chesapeake Bay this summer. By “still large,” they mean it will still rob a large portion of the Bay — the equivalent of 2.3 million Olympic-size swimming pools — of the oxygen needed to support most marine life. But that’s 10 percent smaller than the long-term average of these dead zones, which researchers have been monitoring since 1950.

Attention swimmers, especially the beautiful little ones: scientists anticipate a slightly smaller, though still large, dead zone to form in the Chesapeake Bay this summer. By “still large,” they mean it will still rob a large portion of the Bay — the equivalent of 2.3 million Olympic-size swimming pools — of the oxygen needed to support most marine life. But that’s 10 percent smaller than the long-term average of these dead zones, which researchers have been monitoring since 1950.

Excessive nutrient pollution from the cities and agricultural lands in the Bay watershed causes large algal blooms to form in this shallow estuary. As the blooms decay, they deplete the water of the oxygen needed to support iconic Bay species of oysters, rockfish and those little beautiful swimmers, the crabs and create dead zones in which most animals cannot survive.

A group of scientists monitors the factors contributing to dead zones, and this is their ninth year to release an outlook for the summer. (View historical dead zone data back to 1985 here )

They predict the dead zone this summer will measure nearly 1.4 cubic miles, with about 20 percent of that area predicted to be anoxic, or containing no oxygen at all. Low river flow and lower nutrient loading from the Susquehanna River this spring are contributing to the smaller predicted size.

The Gulf of Mexico released a report indicating its dead zone is not shrinking. Its forecast focuses on square mileage instead of the cubic miles used to measure the dead zone’s volume in the Bay’s shallow estuary.

Scientists predict the scale of the Bay’s dead zone based on models that forecast the volume of low-oxygen waters at three points in the summer. Researchers at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and the University of Michigan developed the models. Their work is sponsored by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and relies on nutrient loading estimates from the U.S. Geological Survey.

The USGS estimates that 58 million pounds of nitrogen were transported to the Chesapeake from January to May of this year, a volume that is 29 percent below average conditions.

“Forecasting how a major coastal ecosystem, the Chesapeake Bay, responds to decreasing nutrient pollution is a challenge due to year-to-year variations and natural lags,” Dr. Donald Boesch, president of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, said in a statement. “But we are heading in the right direction.”

Last year, scientists predicted a larger-than-average dead zone driven by heavy rains in the spring that drove higher volumes of pollutants into rivers and the Bay.

Researchers will measure oxygen levels in the Bay later this year. The dead zone that disappeared earlier than expected last summer made a dramatic comeback in August, threatening species much later in the season than usual.

Bimonthly water quality data can be found on DNR’s Eyes on the Bay website.