This analysis has been updated to reflect the most recent information.

Fishermen along the southeastern U.S. coast report that after years of decline, red snapper are once again plentiful. That’s why anglers are stumped by the results of a new population study showing that this once severely overfished species still isn’t recovering sufficiently.

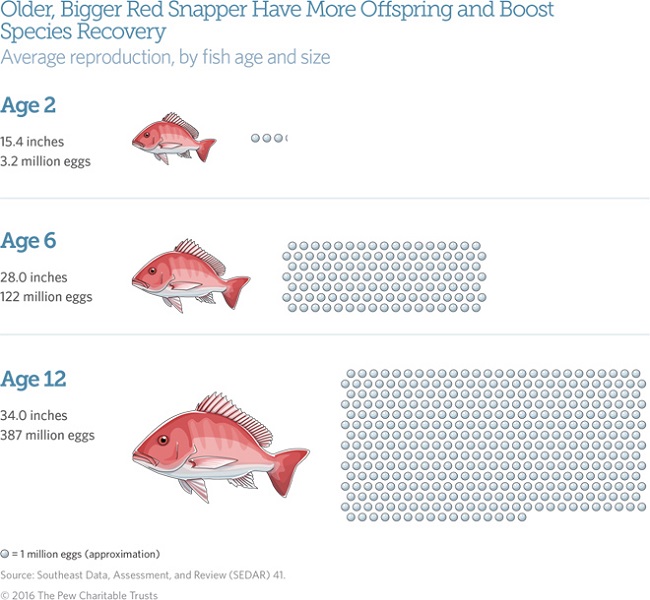

The analysis was conducted by experts from universities, state agencies, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries), and the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council, which governs fishing in federal waters from North Carolina to Florida’s East Coast. The study comes six years into a fishing moratorium designed to help the region’s red snapper population recover. It finds that although the species’ numbers are increasing overall, the population is still below a healthy level, with too few of the older and bigger fish that breed the best. And it notes that despite the fishing freeze, too many red snapper are still dying to keep the recovery plan on track.

But how can this be?

Cause of death: Incidental catch

Although managers made a limited exception to the moratorium—allowing fishermen to catch a small number of red snapper for a few days each summer from 2012 to 2014—the core problem is something else: bycatch. Too many red snapper are caught when fishermen target other snapper and grouper species that also live in deep water. Despite being released, red snapper often suffer such extensive organ damage from the rapid pressure change as they are pulled to the surface that even if alive when released, they can die within days.

The new population study reports that 38 percent of the commercially fished red snapper that are released die this way; for recreational fishing, it’s 28.5 percent. To calculate those numbers, scientists worked on board fishermen’s boats to tag and study released fish, analyzing fishing techniques, where fish were caught, and other factors. Although still too high, those percentages are lower than in the past, thanks to smarter fishing practices such as circle hooks and de-hooking devices that help released fish survive.

New study uses more data

The new study included data collected from fishermen as well as scientific observations of fish primarily caught in traps used for research. Such population studies always contain some level of uncertainty, but a rigorous review process, including evaluation by a panel of independent experts, helps to ensure that they are based on the best available science.

Since the last population study almost six years ago, data collection efforts have expanded. This was particularly evident in Florida, where fishermen, working in cooperation with the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute—the science arm of the state agency that protects and manages fish and wildlife—helped provide information that was incorporated into the latest analysis. In addition, NOAA Fisheries extended its sampling range south to include more red snapper habitat in Florida. The results confirmed that the population still has too few older and larger fish, which are the best breeders.

Although some fishermen have objected to the findings of this and other red snapper research, others—some of whom serve on the South Atlantic council—have accepted the conclusions and offered a suite of ideas to better manage red snapper. The council is planning a stakeholder-driven process to examine the proposed solutions.

The public has a chance to help shape new fishing rules

Some of the suggestions are promising; others will require more study. Council staff members are analyzing the proposals and are scheduled to report back to members at a meeting Sept. 12-16 in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Public meetings are expected to be scheduled after that.

The ideas represent a shift in strategy in response to the study’s unexpected finding that too many fish are still dying. The rebuilding plan calls for full recovery by 2044, so it’s important to get it right in the early stages of the plan. Some highlights of the council’s proposals include:

- Establishing a recreational deep-water fishing season. Now, fishermen are allowed to catch and keep certain fish only during species-specific seasons, which are often staggered throughout the year. If they catch a species at the wrong time, it must be thrown back, but like red snapper, many other deep-dwelling species don’t survive that experience. Fishermen often complain that this is wasteful but that avoiding bycatch of out-of-season deep-water fish is difficult because many snappers and groupers live in the same places and are caught using the same gear.

A recreational deep-water fishing season would operate like a deer or duck season on land, consolidating the time frames for individual reef species and replacing them with a single snapper and grouper season. That would give fishermen the opportunity to keep whatever they caught up to allowable limits, rather than requiring them to throw back many fish that are likely to die. And during the months that the recreational deep-water fishing season is closed, the fish would get a break, theoretically reducing the number of red snapper that are caught incidentally. Council members want scientists to analyze the idea to determine how long a snapper and grouper season might last and the amount of red snapper that could be taken each year. They also want fishermen to weigh in about whether they would favor such a measure.

- Fish stamps. This program would require anglers to purchase a stamp before fishing for deep-water species. The number of stamps could be unlimited, because the primary goal would be to help focus research efforts on anglers targeting red snapper and other reef species, instead of surveying all licensed fishermen. It also would help scientists get a better handle on who, where, and how many people are fishing for the species. This information could better inform analyses of the population status, how many fish are dying as bycatch, and other factors.

- Electronic logbooks. Keeping an electronic record of catch is more efficient than using the paper reports or phone surveys that are the mainstay of current record keeping. Head boat captains who take large groups of people fishing are already obligated to keep the electronic logbooks. The council will vote in the coming months on a separate plan to expand that requirement to charter boat captains who take smaller groups. The proposal is to potentially add individual anglers to the program in the future.

- Limiting entry (the number of permits available) to for-hire captains. By capping the number of for-hire permits, managers could prevent an increase in fishing rates and encourage compliance with the electronic logbook reporting requirements also under consideration. This proposal could affect charter and head boat captains who take clients on trips targeting a variety of federally managed species, not just red snapper. Council members have been discussing this idea for some time apart from red snapper issues and may decide whether to move forward regardless of their actions on red snapper.

- Gear modifications. Some equipment can help red snapper recover from the pressure changes they endure when pulled from the depths and then released. Descending devices, for example, may increase survival rates and could become required gear for all anglers.

- Size, bag, and trip limits. Fishery managers have long used these tools, which limit the size and the number of fish per trip that each person can take. Council members would probably consider these options in connection with other proposals.

- Halting fishing in some red snapper hot spots. In targeted areas where red snapper are found in greater numbers, some council members have suggested a halt to all fishing for snapper and grouper species to reduce bycatch. The council will discuss possible locations and sizes of these hot spots and could request further analyses.

- Changing a benchmark. Some council members have suggested altering an important gauge of the red snapper population’s health. They want scientists to consider whether it is advisable to lower the standard estimate of the amount of egg production needed for the species to effectively reproduce. A scientific panel that advises the council is to report back in a few months, but this could be a risky proposition. More and higher-quality eggs from bigger and older spawners can help repopulate the species faster and provide a safety net in case red snapper have a low-reproduction year or are affected by environmental factors such as availability of food.

Now is the time for fishermen, scientists, and fishery leaders to work together to find solutions that keep the South Atlantic red snapper’s 2010 recovery plan on track and seek opportunities for people to enjoy their favorite catch.

Holly Binns directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ efforts to protect ocean life in the Gulf of Mexico, the U.S. South Atlantic Ocean, and the U.S. Caribbean.